Assessing Ocular Movements

Introduction to Ocular Movements

Ocular movements are essential for aligning the eyes to achieve single, clear, and comfortable vision. They allow us to track moving objects, shift focus, and maintain gaze despite head movements.

Key Terms to Know:

Duction: Movement of one eye.

Version: Simultaneous movement of both eyes in the same direction.

Vergence: Simultaneous movement of the eyes in opposite directions (e.g. convergence).

Sherrington’s Law: Increased innervation to one muscle = decreased innervation to its antagonist.

Hering’s Law: Equal innervation is sent to yoked muscles in each eye for coordinated movement.

Types of Ocular Movements

A. Ductions (Monocular)

Adduction: Towards nose

Abduction: Towards ear

Elevation (Supraduction): Upwards

Depression (Infraduction): Downwards

Intorsion/Extorsion: Rotation around the visual axis

B. Versions (Binocular)

Dextroversion: Right gaze

Levoversion: Left gaze

Supraversion/elevation: Up gaze

Infraversion/depression: Down gaze

Dextro-elevation: up and to the right

Dextro-depression: down and to the right

Levo-elevation: up and to the left

Levo-depression: down and to the left

C. Vergences

Convergence: Both eyes move inward (near focus)

Divergence: Both eyes move outward (distance focus)

D. Other Movements

Saccades: Rapid, voluntary gaze shifts (e.g. reading)

Smooth Pursuits: Tracking moving objects smoothly

Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex (VOR): Maintains eye position during head movement

Optokinetic Nystagmus (OKN): Reflexive response to large moving visual fields

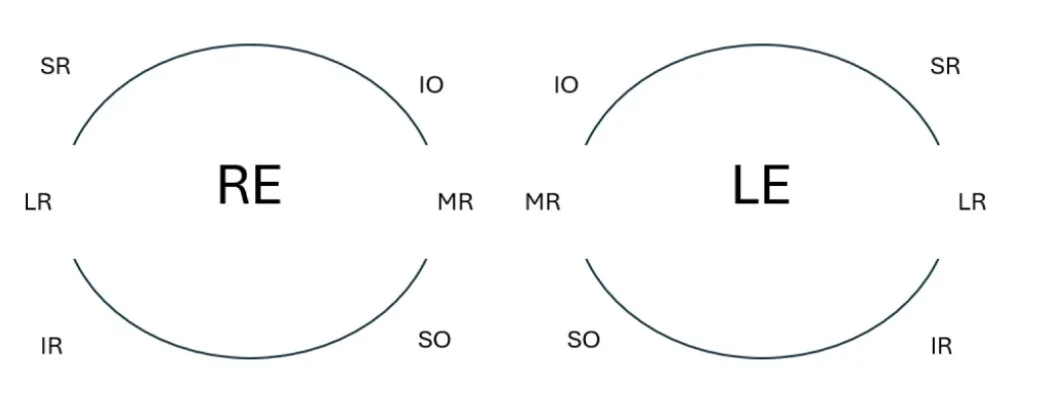

Extraocular Muscles (EOMs)

There are 6 extraocular muscles around each eye:

Medial rectus (MR)

Lateral rectus (LR)

Superior rectus (SR)

Inferior rectus (IR)

Inferior oblique (IO)

Superior oblique (SO)

The muscles are represented diagrammatically in the direction that they are tested in, and this is the direction where the muscle is most active.

The 6 EOMs and Their Actions:

| Muscle | Primary action | Secondary action | Tertiary action | Innervation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superior Rectus | Elevation | Intorsion | Adduction | CN3 |

| Inferior Rectus | Depression | Extorsion | Adduction | CN3 |

| Lateral Rectus | Abduction | - | - | CN6 |

| Medial Rectus | Adduction | - | - | CN3 |

| Superior Oblique | Intorsion | Depression | Abduction | CN4 |

| Inferior Oblique | Extorsion | Elevation | Abduction | CN3 |

Anatomy of the extraocular muscles

There are 4 recti (superior, inferior, medial and lateral). They arise from the common tendinous ring (the annulus of Zinn). This is the thickening of the periosteum at the apex of the orbital cavity. It has an oval cross-section.

The annulus of Zinn encloses the optic foramen and the medial end of the superior orbital fissure

From this common origin, the recti muscles pass forward as a muscle cone and insert into the sclera

From Longest to shortest:

Superior

Medial (Largest)

Lateral

Inferior

Superior Rectus:

The tendinous ring is above the optic foramen and attached to the dural sheath of the optic nerve

It passes forwards laterally and pierces the fascial sheath. The fascial sheath is connected to the sheath of the Levator Palpebrea Superioris by a band of connective tissue

It inserts 7.7mm posterior to the limbus. Its tendon is 5.8mm long

Its line of insertion is curved and oblique

Nerve supply – Superior division of the Oculomotor nerve

Action - When it acts alone: elevation, adduction and intorsion

Inferior Rectus:

The tendinous ring is below the optic foramen

It passes forward laterally and pierces the fascial sheath

The fascial sheath is connected to the sheath of the Inferior Oblique and the suspensory ligament by a band of connective tissue to the lower lid

It inserts 6.5mm from the limbus with a 5.5mm tendon

Its line of insertion is curved and oblique

Nerve supply – inferior division of the Oculomotor nerve

Action - When it acts alone: depression, adduction and extorsion

Lateral Rectus:

Has 2 heads:

1st – the lateral portion of the tendinous ring

2nd – the orbital surface of greater wing of the sphenoid bone

It passes forward and pierces the fascial sheath

The fascial sheath sends off an expansion attached to the lateral orbital wall (the lateral check ligament)

It inserts 6.9mm from the limbus with an 8.8mm tendon

Its line of insertion is vertical

Nerve supply – the abducens nerve

Action - When it acts alone: abduction

Medial Rectus:

The medial portion of the tendinous ring, it is attached to the dural sheath of the optic nerve

It passes forward, close to the medial orbital wall and pierces the fascial sheath which sends off to the medial check ligament

Inserts 5.5mm from the limbus with a tendon of 3.7mm

Its line of insertion is vertical

Nerve supply – the inferior division of the oculomotor nerve

Action - When it acts alone: adduction

The Spiral of Tillaux – the circle which shows the insertions of the recti muscle

There are 2 obliques (superior and inferior)

Superior Oblique:

It arises from the body of the sphenoid bone above and medial to the optic canal. It runs forward between the roof and medial orbital wall, giving rise to a rounded tendon

The tendon passes through a fibrocartilaginous pulley (the trochlear) that is attached to the trochlear fossa of the frontal bone

It bends downwards, backwards and laterally pierces the facial sheath – passing inferiorly to the superior rectus. It expands in a fan shaped insertion into the sclera posterior to the equator of the eyeball

Nerve supply – the trochlear nerve

Action - When acting alone: depresses the eye in adduction, it abducts the eyes and it intorts

Inferior Oblique:

It originates from the front of the orbit (the only one that does this)

It arises from the orbital floor

It passes laterally, posteriorly and superiorly and inserts into the sclera under the lateral rectus. The fascial sheath is attached to the inferior rectus

Nerve supply: inferior division of the oculomotor nerve

Action - When acting alone: elevates the eyes in adduction, it abducts the eyes and it extorts

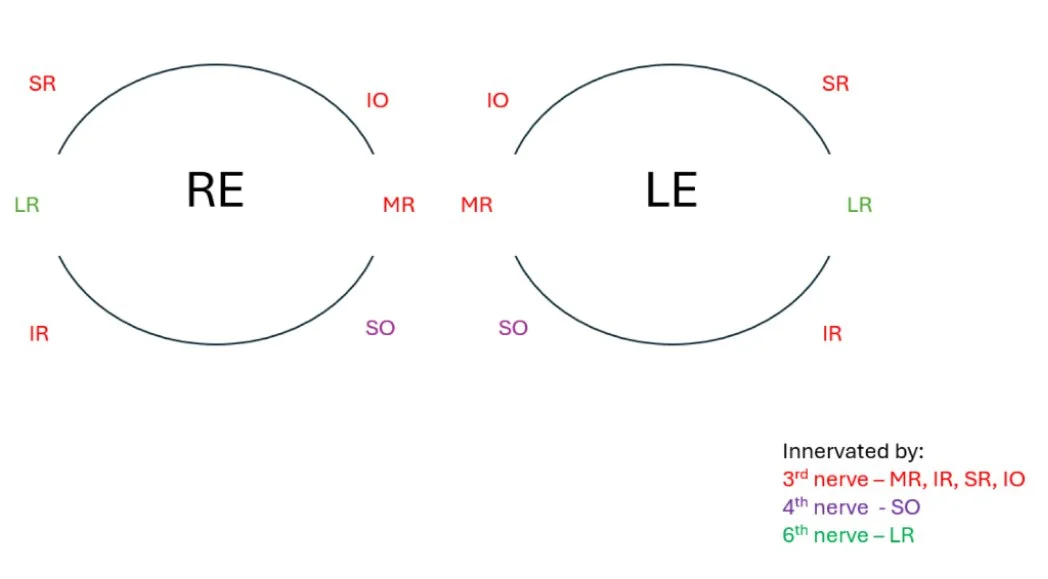

Nerve innervation of the extraocular muscles

4 of the extraocular muscles are innervated by the third cranial nerve. These are the medial rectus, the inferior rectus, the superior rectus and the inferior oblique. The superior oblique is innervated by the fourth cranial nerve and the lateral rectus is innervated by the 6th cranial nerve.

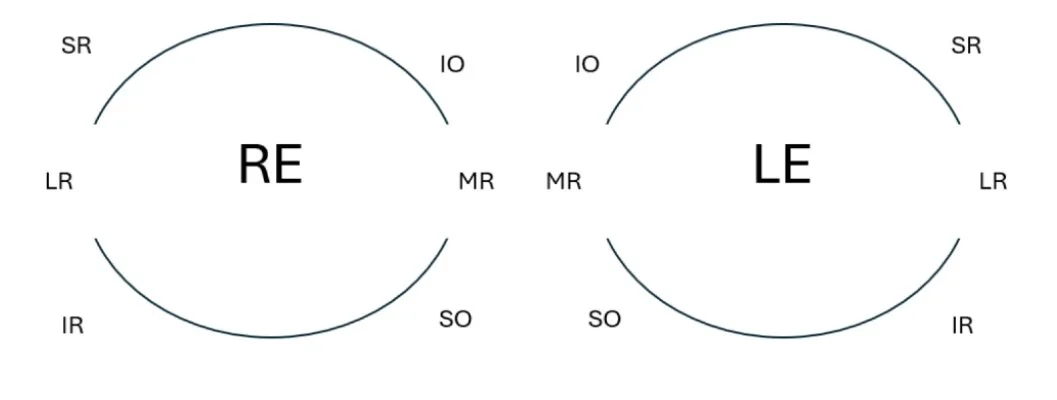

The Nine Diagnostic Positions of Gaze

This tests each EOM in its field of action.

| Position | Eye Muscle Tested |

|---|---|

| Primary | All (in resting tone) |

| Dextro-elevation: up and right | Right SR and Left IO |

| Levo-elevation: up and left |

Left SR and Right IO |

| Dextroversion: Right gaze | Right LR and Left MR |

| Levoversion: Left gaze | Left LR and Right MR |

| Dextro-depression: down and right | Right IR and Left SO |

| Levo-depression: down and left | Left IR and Right SO |

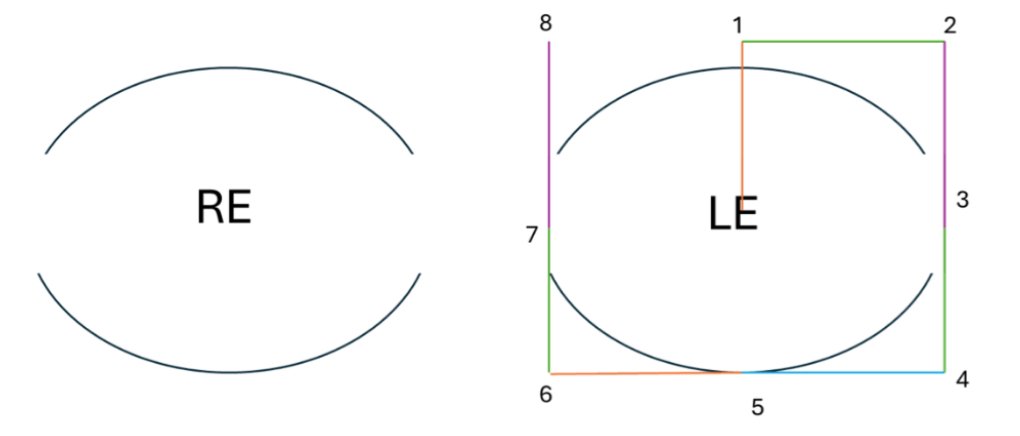

As mentioned before, the muscles are represented diagrammatically in the direction that they are tested in, and this is the direction where the muscle is most active:

Common Mistakes to Avoid:

Confusing which muscle is being tested - learn which muscle is being tested in each gaze position as this helps with your diagnosis

Mislabeling gaze positions (e.g., calling dextroelevation “up and left” etc)

Mixing up right eye and left eye positions. Throughout this guide we have labeled the eyes as you would see them when testing a patient sat infront of you.

Clinical Testing of Ocular Movements

Assessing ocular movements

Before assessing ocular movements, ensure you have done a vision test so you know the level of vision in each eye

You will need a pen torch and an occluder

Make sure the pentorch is bright enough so that you can see the corneal reflections, but not too bright that it makes the test uncomfortable for the patient

Make sure you hold the pentorch in one hand and the occluder in the other, in a way that you are comfortable with.

Explain the procedure to the patient:

Something along the lines of - I will now test your ocular movements. To do this, please keep your head still and only move your eyes to follow the light.

Remember to test without glasses as the frames will get in the way of an accurate assessment

Begin by using your pen torch to assess the patient in primary position - note if the patient has a misalignment (eg esotropia/exotropia, and note which eye)

Perform a cover-uncover test by covering one eye and observing the movement of the uncovered eye when the patient alternates fixation.

Now move your pen torch to either dextroversion or laev-oversion - make sure you reach the extreme end of the gaze. Assess for any restrictions. Also note any nystagmus that might be present (and which type if you have learnt this)

This is assessing the versions for each gaze

Return to the primary position. And repeat the gaze with one eye occluded at a time

This tests the duction for each eye. This helps you differentiate between neurogenic and mechanical restrictions (as the movement will improve in a neurogenic but not a mechanical).

Repeat this for all other positions of gaze, making sure to return to the primary position before moving on to the next gaze.

A key thing to note is that you must be able to see the corneal reflection at the extreme point of gaze. If your light is obstructed by the patient's nose/facial features, then the patient can't see the light either and you are not testing the gaze correctly.

Record your results clearly on an ocular movements diagram, using the correct annotation for what you saw.

- is used for an underaction

+ is used for an overaction

Arrows are used for up/down shoots

Hashed lines are used for restrictions

Interpret the results, considering the coordination, smoothness, and limitations in eye movements, which may point to a specific ocular motility disorder.

Tips

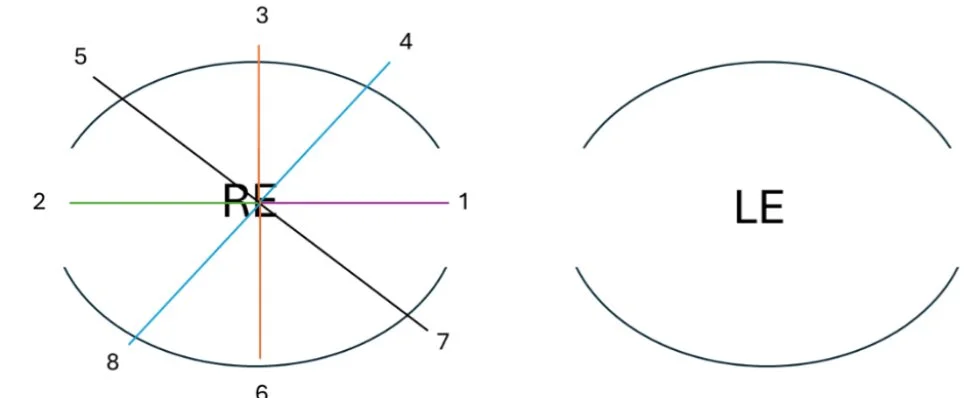

Ideally you would want to assess the ocular movements in a pattern similar to this; starting from the middle.

As you do it more often, you will find a rhythm that works best for you. Always remember to return to the primary position before moving to the next gaze.

You do not want to assess them like the following:

Or any other variation, where you move directly from one gaze to the other. As this might cause you to miss underactions.

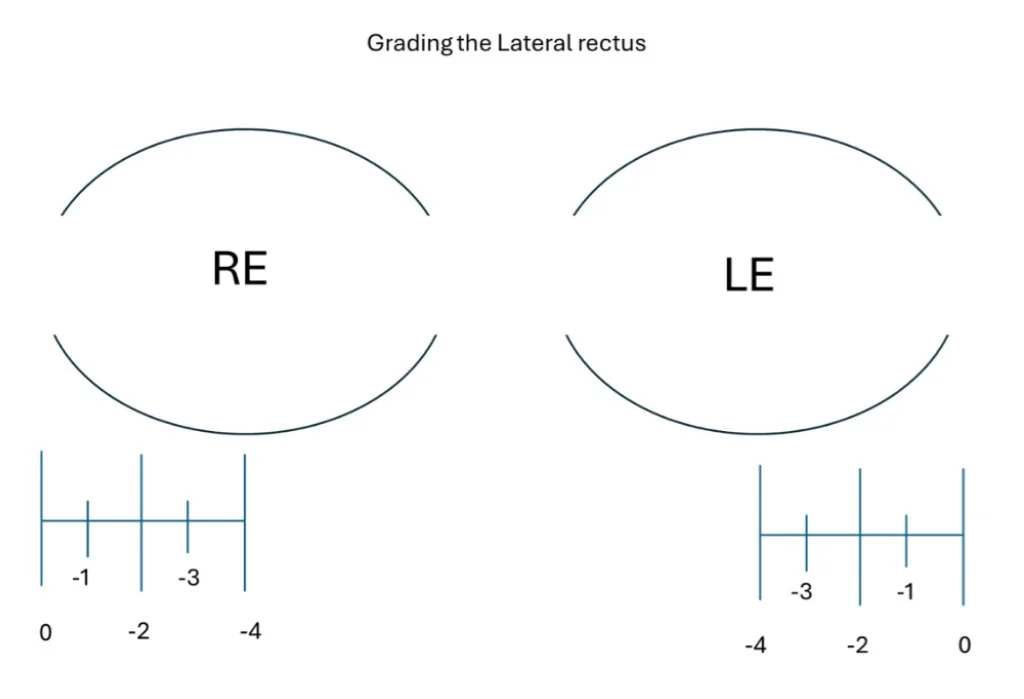

The best way to think about grading ocular movements, is to think of a scale from 0 to 4. As you move from primary position to the extreme gaze of any position, move your pen torch in ¼ intervals (as demonstrated by the diagram below, for the lateral rectus). If the eye stops moving at any point, then this correlates with the amount of restriction. If the eye does not move past the midline, this would be a -4 restriction.

Laws of eye movements

Position of the eyeball

Primary position – patient looking straight ahead

Secondary position – related to the movements of the rectus muscles

Tertiary position – related to the movements of the oblique muscles

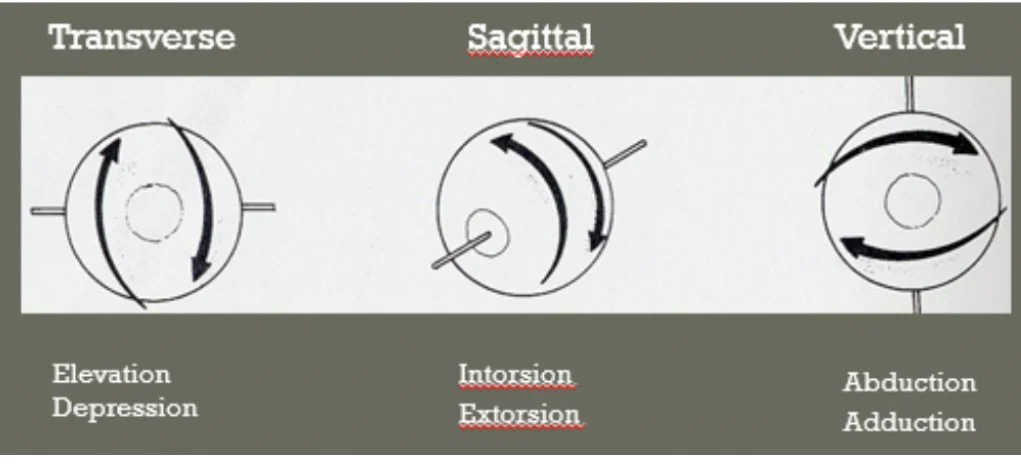

Fick’s axes

The centre of the cornea is used as the anatomic anterior pole of the eye

X axis (Transverse) – passing through the centre of the eye at the equator causing vertical rotations

Y axis (Sagittal) – passing through the pupil causing involuntary torsional rotations

Z axis (Vertical) – causes horizontal rotations

Donder’s law

To each position of the line of sight belongs a definite orientation of the horizontal and vertical retinal meridians relative to the coordinates of space

Orientation depends solely on the amount of elevation/depression/lateral rotation of the globe

The orientation of the retinal meridians related to a particular position of the globe is achieved irrespective of the path the eye has taken to reach that position

After returning to its initial position, the retinal meridian is orientated exactly as it was before the movement was initiated

Listing’s law

Each movement of the eye from the primary position to any other position involves a rotation around a single axis lying in the equatorial plane (Listing’s plane)

Listing’s plane – fixed in the orbit and passes through the centre of rotation of the eye and its equator when the eye is in primary position

The axis is perpendicular to the plane that contains the initial and final positions of the line of sight

Hering’s Law

Equal and simultaneous innervation is sent to yoked muscles in both eyes to produce coordinated binocular movement.

In summary: muscle pairs receive equal innervation (this relates to the contracting muscle and its synergistic muscle in the other eye). If one muscle is underacting (due to a weakness or a restriction), this causes its synergistic (partner) muscle to overact.

Example: a patient as an isolated right superior oblique weakness due to a 4th nerve palsy. This means that when testing that gaze, the right sight superior oblique underacts (due to the weakness. The left inferior rectus is acting as it should but due to

Sherrington’s Law of Reciprocal Innervation

When an agonist muscle contracts, its antagonist is reciprocally inhibited in the same eye.

Example of Hering’s law and Sherrington’s law in action

The 4th cranial nerve innervates the superior oblique (SO) muscle.

A right 4th nerve palsy = weak or absent action of the right SO.

The primary actions of SO: intorsion, depression, and abduction.

So, the main clinical sign is underaction of the right SO, especially on down and in gaze.

What You See Clinically:

1. Underaction of Right SO

In down-and-in gaze (e.g. left downgaze), the right SO fails to depress the eye properly.

This shows up as a limited or slow movement downward in adduction.

2. Overaction of Left Inferior Oblique (IO)

The contralateral antagonist to the SO is the left IO (which elevates the eye in adduction).

This muscle appears overactive — the eye elevates more than it should in left upgaze.

But why?

Sherrington’s Law (of reciprocal innervation)

When a muscle contracts, its direct antagonist is inhibited.

In right SO palsy, the SO is weak and doesn’t contract fully.

So, the right inferior oblique (IO)—the antagonist—is not properly inhibited, leading to apparent overaction.

This can look like the eye is elevating too much in adduction (IO overaction).

Hering’s Law (of equal innervation)

Yoked muscles in both eyes receive equal neural input for coordinated binocular movement.

If the right SO is weak, more innervation is sent to try to get it to work.

But Hering’s Law means this extra innervation is also sent to its yoke muscle: the left inferior rectus (IR).

The left IR then depresses the left eye too much, leading the brain to increase IO activity to compensate and maintain vertical alignment.

This can cause the left IO to overact in up-and-in gaze, even though it’s not truly “stronger”—it’s just receiving excess input due to Hering’s Law.

In Summary:

| Muscle | Effect Seen | Law Involved |

|---|---|---|

| Right SO | Underaction | Direct nerve palsy |

| Right IO | Overaction | Sherrington's law |

| Left IO | Overaction | Hering's law |

• Hering’s Law: Equal and simultaneous innervation is sent to yoked muscles in both eyes to produce coordinated binocular movement.

• Sherrington’s Law: When an agonist muscle contracts, its antagonist is reciprocally inhibited in the same eye.

Let me know if you want quick mnemonics for them too!

We have created a handy PDF with all the relevant information above, aswell as tips on how to troubleshoot common mistakes and a quiz to test your knowledge. Download the guide for free here.